Quick – show of hands – tell me everything you know about Eldridge R. Johnson….well, if you’re poking around this website, you probably have heard of him, but many people have not. If you’re one of the ‘nots’ — perhaps you’ve heard of his company The Victor Talking Machine Company which he founded 1901 (or at least its later incarnation as RCA-Victor). Perhaps you’ve heard of the Victrola, and in fact you might refer to every type of old-fashioned, wind-up record player as a Victrola. And surely you’ve seen Nipper the Dog, one of the first and most successful trademarks in business and advertising history. But this guy with the funny name and that – what’s he got to do with talking machines, fox terriers, and, for that matter, EMI?

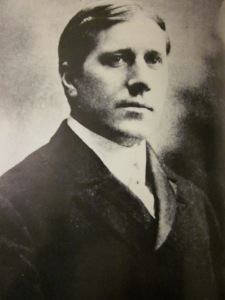

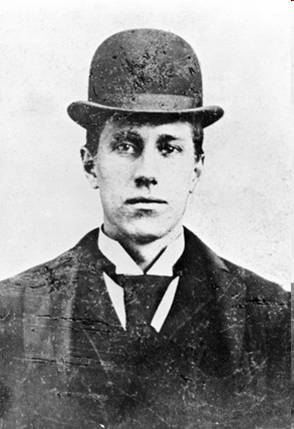

Eldridge R Johnson around age 35

Eldridge R Johnson around age 35

Eldridge Reeves Johnson (1867-1945) is an obscure figure in music history, and his name is certainly not as recognisable as Thomas Edison or Alexander Graham Bell. It’s a bit of his own fault, really, as Johnson, while promoting his company and its products vigorously, himself stayed in the background – unlike his contemporary Edison, or modern moguls such as Bill Gates or Richard Branston, whose names are as well-known as their products. Nevertheless, Johnson founded one of the ‘Big Three’ early record companies – The Victor Talking Machine Company (1901-1927) held its own against Edison Records (1888-1929) and Columbia Records (1888-present). The Victor Company was a sister-company with the Gramophone Company (independent from 1897-1931) in the UK; the Gramophone Company merged with the Columbia Graphophone Company in 1931 to become EMI, so Johnson and the Victor Talking Machine Company are part of EMI’s pedigree.

Over ten instalments, we shall present 10 Interesting Facts about Eldridge R. Johnson, one of the founders of the modern recording industry. Before Johnson Fact #1, however, here’s a little background on the man himself.

Johnson was born in 1867 in Wilmington, Delaware, USA, and grew up about 60 miles further south in Dover, Delaware, then a rural community. He went to high school at the Dover Academy in Dover, Delaware, now part of the grounds of Wesley College [http://www.wesley.edu/], and he hoped to go to university. It’s unknown which school or course of study he had in mind; when Johnson, then aged 15, approached his high school principal about going on to higher education, he was told he was ‘too stupid’ to attend university, and should go to trade school instead.

Johnson was gutted, and this comment stuck with and influenced him the rest of his personal and professional life. He was put on a train and sent north to be apprenticed to a machine shop in Philadelphia, and, according to the biography written by his son, ERJ cried all the way to his destination.

Was Johnson ‘too stupid’? As a boy, he asked a lot of questions – at home and at school. Nowadays this is regarded as the sign of an inquisitive mind, praised, and encouraged, but in those days, asking so many questions was interpreted as being daft.

Nevertheless, despite the low pay and long hours initially, Johnson applied himself to the work and his apprentice job, and to his displeasure (initially) he turned out to be quite mechanically apt. He worked in Philadelphia, then became attached to the Standard Machine Shop in Camden, New Jersey (where he filed his first patent to improve a bookbinding machine at the shop – Johnson seems to have been that guy who shows up in a place and quickly fixes all of the mechanical problems plaguing the company). At one point he went West to seek his fortune as the owner of this new shop planned to leave the business to his own son, but after a few adventures, Johnson realised there was more opportunity for work back on the East Coast. He returned to the little shop in Camden and inherited it after all, as the son had died suddenly and the owner was in financial peril. So Johnson took over the little shop and began to build a reputation for himself in the area as a mechanical engineer. Although he devoted himself to his work, he was also driven to educate himself in the classics and refined arts, and his diaries reveal later trips to the opera, visits to museums, and lists of literary texts to read. He never stopped asking questions, and turned his inquisitiveness into a business success – whether he was asking his workers about their lives and working conditions, or his customers about suggestions they had about or wanted from his products.

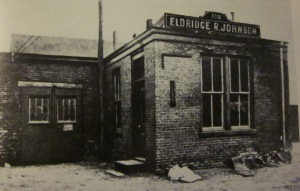

This same, small machine should would eventually be surrounded by the Victor Talking Machine factory complex.

Johnson’s shop in Camden in the 1890s

Johnson’s shop in Camden in the 1890s

Berliner’s original eggbeater gramophone

Berliner’s original eggbeater gramophone

Berliner had patented his gramophone in 1887, but he himself was no mechanic – he wanted a spring-loaded motor for the machine to make it fully automatic, more than just a toy, as this would give him the edge in the extremely competitive world of sound-recording. Learning of Johnson’s mechanical skills, he sent the machine to the workshop in Camden. Johnson gave the little gramophone a look over, and took on the job – adding a spring-loaded motor (of his own design) would be quite easy.

Berliner gramophone with Johnson’s spring-motor

Berliner gramophone with Johnson’s spring-motor

Here are two clips of Berliner’s original gramophone in action: the egg-beater in action and Johnson’s added motor:

…and another short clip (in French) showing the eggbeater, then the improved gramophone, with a shot of Johnson’s clockwork motor with the cover off:

This invention alone would have sufficed to ensure Johnson’s role in the history of the recording industry: not only did this motor free the user from having to hand-crank the machine, but it also standardised the recording speed at about 78 rpm – instead of a toy, the gramophone could be regarded as a proper tool for recording and promoting both popular and classical music and artists.

Of course that was to come – Johnson’s initial impression of that first gramophone was less than enthusiastic; he famously said that the sounded like “a partially educated parrot with a sore throat and a cold in the head.”’ Nevertheless, Johnson was intrigued and went into a subcontractor partnership with Berliner, building gramophones and gramophone parts. He also improved the quality of the recording process on the gramophone by experimenting with electroplating wax disks to make more precise and sturdier master matrices – the wax of which, by the way, came from melted down wax cylinders made by rival Edison.

This partnership also meant that he also entered into association and later partnership with Berliner’s UK component, The Gramophone Company (headed at that time by William Owen).

William Owen, head of the Gramophone Company around 1900

William Owen, head of the Gramophone Company around 1900

Almost at once he was embroiled in the Byzantine politics of betrayal, backstabbing, and litigation involving Berliner’s company and a breakaway company called Zonophone (who were, in effect, attempting to pass a law forbidding Berliner to sell his own products.)

Long story short – Johnson won a successful lawsuit against Zonophone, saving Berliner, The Gramophone Company, and Johnson himself from financial ruin. Johnson’s original company, The Consolidated Talking Machine Company, became in 1901 The Victor Talking Machine Company, in cooperation and with the blessing of the Gramophone Company in England.

Between 1901 and 1927, Victor was one of the most successful businesses in the world. Johnson’s motto for the company was its ‘secret process,’ that is, ‘We seek to improve everything we do every day.’

Between 1901 and 1927, Victor was one of the most successful businesses in the world. Johnson’s motto for the company was its ‘secret process,’ that is, ‘We seek to improve everything we do every day.’

Johnson’s motto serves as the mission statement at the Johnson Victrola Museum, Dover, Delaware, USA (author’s photo)

Johnson’s motto serves as the mission statement at the Johnson Victrola Museum, Dover, Delaware, USA (author’s photo)

This motto reveals much about his own personality, drive for success, and care for his employees and customers. And because the company was his top priority, this motto provides a clue why we don’t associate Johnson with Victor as we might associate Nipper, the great singer Enrico Caruso, or the Victrola itself.

Johnson was a multi-millionaire very quickly with his company; when he finally sold Victor in 1927, he was worth close to $29 million. Problems with melancholia and depression had affected his relationship with his business over the years, and concerns that Victor was falling behind the competition with radio led him to sell his company 1927 (Victor was purchased by RCA in 1929), and he lived the rest of his life as a generous philanthropist while happily indulging his passion for his yacht and sailing. He died in 1945.

One thought on “Victor Ludorum. The Forgotten Man of Music History: Eldridge R.Johnson”